Flickr CC by 2.0 - Franz Conde

Related Posts:

> How to reduce conflict with motorists and pedestrians

Details:

- I've provided my summaries and comments under each chapter of the book.

1. Revelation: The worst day I ever had and why it gave me faith in humanity

- Eben Weiss recounts how the brief, temporary change in stranger's street interactions after the September 11th terrorist attacks gave him faith in people's underlying goodwill, respect and compassion:

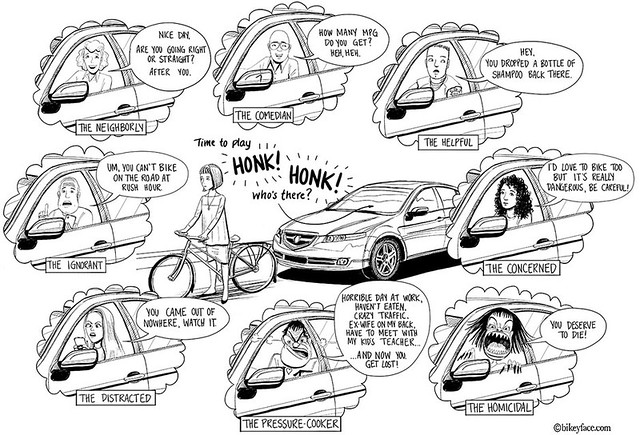

When a driver intentionally swerves into me while I'm riding my bicycle, I try to assuage my rage by remembering that, beneath the callus, the compassion is still there... that knowledge has given me the strength to negotiate many frustrating situations.- Yet, the fact that an event as significant as the 9/11 tragedy provided only brief respite from the callous indifference and selfishness on the roads suggests that these commuting behaviours are very sticky and often subconscious. In particular, driving an enclosed, motorised vehicle is an activity which consistently brings out the some of the most selfish and disrespectful aspects of human behaviour (even when cyclists get behind the wheel). There are both obvious and more subtle or complex reasons for this. John Cleese points out that when humans can't see each other's faces and communicate via their expressions this leads to conflict. See: The Human Face - The cause of road rage. Bikeyface visually illustrates the same barrier to communication presented by cars through a range of common motorist-cyclist interactions:

As infuriatingly bad as our interactions on the street can be, it's essential to know that this compassion is what lies beneath our frustration. More than laws and better infrastructure and more bike lanes, it's getting in touch with that compassion and being able to draw upon it that will bring us the happiness that so often eludes us.

Bikeyface - Talking to Machines

- The psychology of commuting behaviour and the significant variations in certain attitudes based on mode (particularly driving vs the other modes) is a rich area of insights that don't appear in this book. For example, see this review of research by Damien Adler: 774 ABC Melbourne: Psychology: Why we don't like cyclists. It found the following:

(a) Cyclists are not ranked highly as a concern that's present in driver's minds

(b) When drivers are specifically asked about cyclists most have a negative opinion

(c) Commercial drivers had the lowest opinion of cyclists

(d) Drivers think cyclists are unpredictable and ignore the road rules

(e) Drivers criticise cyclists for minor transgressions but are more forgiving of other road users

(f) When cyclists drive they tend to adopt this typical driver perspective

(g) Drivers respect other vehicles in accordance with the other vehicle's size

(h) A negative experience with a cyclist tends to be generalised across all cyclists (unlike with drivers)

(i) Once we have a negative attitude our mindset looks for further confirmation of that attitude

(j) Drivers see cyclists as an out-group that doesn't belong on the road or have the same rights to it

(k) Drivers perceive cyclists as breaking road rules even when cyclists are riding legally (they often don't understand cyclists can pass on the left, filter through traffic, occupy any part of the bike box at intersections, make hook turns at any intersection, etc.)

(l) Drivers are fearful of making small mistakes or oversights that might critically injure cyclists

(m) Any inconvenience caused by a cyclist causes a higher level of annoyance than if caused by a driver

Damien Adler also lists three main things cyclists can do to minimise conflict:

(a) Follow the same road rules as other road users

(b) Try to ride as predictably as possible and signal

(c) Try to minimise inconvenience to other road users

Damien advises motorists to contribute to less conflict by:

(a) Not generalising the behaviour of one cyclist to all cyclists

(b) Paying attention to positive examples of lawful and courteous cycling behaviour

(c) Imagining the cyclist you are annoyed with is someone you know and care about and temper your anger and driving be

(d) Pausing before reacting and preventing road rage.

- David Hembrow, who publishes A View From The Cycle Path, would argue with Eben that quality cycling infrastructure and bike-friendly policies are the key to more respect and less stress and conflict. Unravelling the different modes of transport (bikes, cars, public transport) through an efficient grid of safe cycle paths is exactly why the Netherland's has not only the world's highest cycling rates but also the least conflict between cyclists and other road users. See: A Toot and a Wave. Dutch cyclists are not an out-group. Car horns are not used as weapons

- Of course, Eben, like myself, writes advice for dealing with the "here and now" realities of cities like New York and Melbourne. We'd agree that courtesy, respect and not responding in-kind to aggression makes for a much more pleasant experience getting around by bike, with a lot less conflict and frustration. This is a significant, conscious mindset switch from the instinctive response to aggression but I would argue it's based mostly in self-interest, not compassion.

- Rather than "getting in touch with their inner compassion", I think most cyclists are more likely to be driven by their natural self-interest in achieving stress-free commuting and more pleasant interactions with other road users. I've discussed some of the practical ways cyclists can achieve "cycling zen" here: How to reduce conflict with motorists and pedestrians

2. Communion through commuting: Why commuting is the portal and the bicycle is the tool

- Eben argues that our attitudes about commuting are primal (like sex and childbirth) and that our journeys have always been beset by feelings of apprehension and fear thus:

In our highly refined and abstracted age, the simple business of getting from one place to another is one of the remaining areas of life in which a perfect stranger might scream at another.- However, despite the millions of years of these primal emotions and behaviours, he suggests that our conscious decisions and attitudes to commuting provide the greatest opportunity to change the way we relate to each other: with respect replacing conflict and love supplanting irritation.

Changing the way we commute is really the best opportunity we have to try and effect change for the better - not just by avoiding "accidents," but by generally practising compassion and treating others well. Our commute is the void between our homes and our jobs and our recreation and our socializing - all arenas in which mutual respect and compassion are (ideally) already the norm - and if we can fill that void with benevolence instead of indifference, we can embark upon our commute with excitement instead of apprehension and emerge on the other side of it even happier than we were when we started. We don't even need bike lanes or federal funds or more efficient vehicles for that - we can do it using exactly what we have. I really believe we can commute ourselves to enlightenment.- The book then anoints cyclist commuters as being in a unique position to change commuting culture because: (a) cyclists choose their commuting mode because they are seeking more happiness from commuting; (b) cyclists are menaced by cars and menacing to pedestrians and so understand both sides of the equation; (c) cyclists also drive and walk and get multi-modal integration; (d) nobody likes cyclists and they have the most to lose:

The challenge then is to be the best cyclists we can, to rise above the primal nature of commuting, and conquer this Last Frontier of Hostility and Indifference.- However, singling out cyclists as the leading agents of change misses the primary sources of this conflict and the ways it can be reduced by all road users. Mia Birk, the former bicycling coordinator in Portland, provides genuinely constructive suggestions for building consideration between all road users and reducing conflict via better infrastructure and design:

This, along with bike lanes and other infrastructure improvements, helped send a message to people on bikes: “Yes, you are welcome. We are evolving our transportation system to reflect your needs." Many stop signs should be supplemented with yield signs and markings specific to cyclists, for example. We need more green bike boxes to reduce right-turn conflicts at intersections and a robust network of low-stress, comfortable, convenient bikeways. A number of signalization techniques will help as well. These include bike-specific traffic signals, quicker response times for bike- (and pedestrian-) activated signals, coordinated signal timing, a few seconds of “pre-green” time to allow people on bikes to mount, and bike-specific traffic signals.

No matter where I go, the lesson is the same: if we treat people on bikes as legitimate users of the transportation system with appropriate infrastructure, behavior improves. Upgrading infrastructure is the government’s job. The rest – shaping up our own behavior – is up to us.See:

> Law Breaking Cyclists: The Answer

> Law Breaking Cyclists: The Answer, Part 2

3. Who we are, how we got this way, and how to get to where we need to be

- This chapter comprises of an idiosyncratic summary of world history as it relates to journeys and the resulting "cultural baggage of commuting" that we inherit today. It doesn't make much sense and so I won't bother discussing it as the author doesn't take it seriously either:

Sure, it may seem like a bold claim that our commute is essentially a reduction of all of humanity's travels, interactions, and beliefs from the beginning of history until today, but I maintain that it is true.4. Annoying cyclist behaviour

- This chapter discusses the ways cyclists inconvenience and annoy fellow cyclists and explains why they should desist: (a) Salmoning - riding the wrong way; (b) Shoaling - the habit of stopping at an intersection ahead of the existing cyclists rather than behind them; (c) Racing - competing to pass or stay ahead of fellow commuters; (d) Wheelsucking - sitting on another commuter's back wheel to save energy or launch an attack; (e) Circling - riding around in circles at red lights rather than stopping; (f) Trackstanding - balancing on the pedals while remaining stationary at an intersection; (g) Substandard equipment - not having properly functioning brakes or lights; (h) Blowing your noise or spitting without checking behind you.

5. Annoying driver on cyclist behaviour

- Provides a summary of common driver behaviours that adversely impact cyclists and should be minimised. These include: (a) The right hook; (b) The wayward door; (c) Stopping or parking in the bike lane; (d) Driving distracted.

6. Annoying cyclist on driver behaviour

- This chapter mostly discusses one way in which cyclists aggravate motorists which Eben calls "passive assault" - it occur when a cyclist puts a motorist in a position of having not to kill him. For example, darting out suddenly in front of a car or blowing through a red light with other traffic forced to brake. Eben's main point is that people rely on mercy and common sense to preserve each other's safety and that dangerous cyclist behaviour exploiting these instinctive "do no harm" reactions breeds resentment.

7. The backlash against cycling

- Discusses the poor opinions (derogatory, low status, hapless, dorky, self-important, luddite, freakish, childish) many non-cyclists have of cyclists - especially those who ride on the road or for transport and why this is a problem.

8. How cycling is sold

- No insights or ideas here. Just some basics about consumerism, types of bicycles and cycling image (e.g. cycle chic).

9. Bikes vs Cars: What are we fighting for?

- Eben argues the bike vs car debate is fictional, that both are necessary in modern cities and that the only sensible solution is for them both to be used in complementary ways. He argues that cyclists need to accept the legitimacy of cars and act accordingly and then hope this behaviour is reciprocated.

10. Why people don't ride

- Given the benefits of bike commuting for individuals, citizen relations and city life, Eben asks: "Does it make sense to try to convince people to live as we do and to embrace the bicycle? Is it even possible?" Most transport cyclists will find his answer a little disappointing:

The short answer is "no freaking way." In fact, it's because I enjoy cycling so much that I know there's no freaking way most non-cycling people are suddenly going to start riding a bicycle, since it's my love of it that makes me put up with the indignity of cycling in a society that hates me for doing it and doesn't even want to give me my own tiny little lane.- However, Eben goes on to point out that while many people are unreachable there are others who just need existing barriers removed and will then start biking when and where it makes sense to them. He gives, as an example, some of his apartment block cohabitants starting to ride once there was a convenient place to store their bikes.

Just take a look around you the next time you're stopped at a red light... almost everybody you see will be very difficult to imagine on a bike. They're wearing suits; they're ample of frame; they're sending emails and putting on makeup and eating entire boxes of Chicken McNuggets.

11. The alchemy of the mundane

- The idea of learning to derive joy from mundane, regular activities is introduced. For example, while your bike commute to work may not be naturally pleasant like a recreational ride along a river in the sun, you can find ways to extract satisfaction from it through habits of mind.

- The tricks that apparently help include: (a) Clearing your mind of mental baggage and anxiety before you set out on your commute; (b) Set a goal not to get angry on your commute; (c) Embrace negativity and try to figure it out and rise above it; (d) Treat others well on your commute and enjoy the pleasant interactions and gratitude.

12. My overall summary

- The book started out with grand ambitions and I was curious to read some specific, fresh ideas and insights on how cyclist commuters should approach their interactions with other road users while getting around by bike. However, as you may have noticed from the progressively shorter chapter summaries, the original thesis didn't go anywhere interesting and is muddled by irrelevant diversions. There really wasn't much else of note to comment on. If you are interested in this book because of the writing style in BikeSnobNYC, I would suggest you'll get more out of the blog as the format is better suited to Eben's humour.

Further Info:

Chronicle Books - Bike Snob

Goodreads - The Enlightened Cyclist: Commuter Angst, Dangerous Drivers, and Other Obstacles on the Path to Two-Wheeled Transcendence

774 ABC Melbourne: Psychology: Why we don't like cyclists

YouTube

> The Human Face - The cause of road rage